Date: Saturday, 26 March 2022

Time: 7:30 p.m. MST

Location: Helena Civic Center

Watch live on YouTube. Saturday, 26 March 2022

Indulge in Elgar’s profoundly expressive Cello Concerto with worldwide acclaimed Israeli-American Cellist Amit Peled. Then experience the music that caused a riot – the provocatively primitive and viscerally powerful Rite of Spring by Stravinsky.

Currently in his nineteenth season as Music Director of the Helena Symphony Orchestra & Chorale, Maestro Allan R. Scott is recognized as one of the most dynamic figures in symphonic music and opera today. He is widely noted for his outstanding musicianship, versatility, and ability to elicit top-notch performances from musicians. SYMPHONY Magazine praised Maestro Scott for his “large orchestra view,” noting that “under Scott’s leadership the quality of the orchestra’s playing has skyrocketed.”

About the Guest Artists

Keeping You Safe in the Concert Hall

Due to the recent increase in COVID-19 cases and new variants emerging in Lewis and Clark County and the United States, the Helena Symphony will take necessary precautions to keep our musicians, staff, and audience protected. The Helena Symphony will continue to follow CDC guidelines throughout Season 67 and monitor the daily transmission rates within our county. When the transmission rate is high or substantial, audience members will be required to wear a mask while in the concert hall. On concert nights when the transmission is moderate or low, individuals will be encouraged to wear a mask, but are not required to do so.

Each member of the Helena Symphony Orchestra & Chorale will be tested prior to rehearsals and prior to each concert. This will ensure each musician present on stage is negative for COVID-19. The Helena Symphony will continue to work closely with the county health department and the city of Helena throughout the Season to ensure the safety of our musicians, staff, and audience. If you have questions about how the Helena Symphony will be adapting to the evolving COVID-19 situation this Season, please call our office at 406.442.1860.

About the Program – By Allan R. Scott © edited by Brain D. Sweeney

Parallel Events / 1919

Treaty of Versailles signed, ending World War I

Nazi Party and Fascist Party are formed

Prohibition begins in United States

Gershwin’s first musical La Lucille premieres

U.S. begins passenger flights

Telephones can be dialed from home

Jack Dempsey becomes the heavyweight champ

Jazz singer Nat “King” Cole, Baseball great Jackie Robinson, author J.D. Salinger, and humorist Andy Rooney are born

Theodore Roosevelt and industrialist Andrew Carnegie die

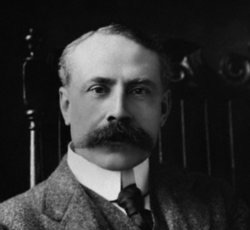

SIR EDWARD ELGAR

Born: Broadheath, England, 2 June 1857 Died: Worcester, England, 23 February 1934

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 Elgar’s Cello Concerto is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, optional tuba, timpani, and divided strings. Duration: 30 minutes

Parallel Events / 1913

Woodrow Wilson becomes 28th U.S. President

Henry Ford begins first moving assembly line

Panama Canal opens

Abolitionist Harriet Tubman dies

Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks, athlete Jesse Owens, composer Benjamin Britten, singer Perry Como, union leader Jimmy Hoffa, football coach Vince Lombardi, actors Burt Lancaster and Lloyd Bridges, and U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford are born

Brillo pads are introduced

IGOR STRAVINKSY

Born: Oranienbaum, Russia, 17 June 1882 Died: New York, USA, 6 April 1971

Le Sacre du Printemps (Rite of Spring) Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is scored for two piccolos, three flutes, alto flute, four oboes, two English horns, three clarinets, E-flat clarinet, two bass clarinets, four bassoons, two contrabassoons, eight horns, two Wagner tubas, four trumpets, high trumpet, bass trumpet, three trombones, two tubas, timpani, bass drum, tambourine, cymbals, antique cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, güiro, and divided strings. Duration: 30 minutes